by William McGimpsey

Introduction

This paper explores the challenges facing New Zealand’s news media. It identifies media bias as a key problem for New Zealand democracy and society, and argues for a mixed model of regulation, with a firmer regulatory approach implemented to address bias in New Zealand’s public media entities – 1News and Radio New Zealand – while leaving private media largely unregulated.

Background

The health or otherwise of New Zealand’s media has been a topic of serious political discussion for some time now. The growth of the internet and social media has disrupted the industry and led to fundamental changes in the way people consume news and journalistic content. The old pattern, of most New Zealanders consuming news from similar sources, has been disrupted. Now, New Zealand’s news and information landscape has been fractured, and different political and ideological tribes increasingly get their information from competing ‘news ecosystems’. Many analysts worry that we now no longer even share the same set of facts and that the different media spheres we belong to are driving increased partisanship and harming social cohesion.

More recently, the close relationship the previous Labour government cultivated with the mainstream media has brought the media’s reputation into further disrepute. This includes claims that the media’s acceptance of the public interest journalism fund (PIJF) money amounted to a bribe, and the large amount of advertising the government provided to the media to support the COVID response may have biased its coverage to an even greater extent than previously. In fact, these developments led prominent former 1News broadcaster Peter Williams to make the comment that New Zealand’s mainstream media was “bought and paid for”.

Mainstream media is also under increasing financial pressure: Newshub, which was New Zealand’s second largest television news provider and 1News’ major competitor, closed at the end of July 2024. Subsequently Stuff group began producing 3 News, and restructured its business internally, including by closing several provincial newspapers. NZME has undergone major newsroom reorganisation and job cuts, and TVNZ announced cutbacks including the elimination of longrunning shows such as Fair Go and Sunday. The latest development is the Broadcasting Standard’s Authority’s decision to try and extend its regulatory apparatus to cover online media providers such as The Platform and RCR. These developments make it timely to consider the issue of media bias and regulation once more.

What is the proper function of the news media in a liberal democracy?

In order to understand and assess whether there is a problem with the current state of New Zealand’s news media, and what, if anything, should be done about it, we need some sort of model that enables us to understand the purpose a news media fulfils in a democratic society.

To explain the role of the media, I will draw an analogy between it and the education system.

All modern democratic countries have a compulsory education system where youth are schooled from the time they are young children through the majority of their teenage years. Why, in liberal democratic societies, where consent is the yardstick for determining the legitimacy of various social institutions, do we force our kids to begin their lives through a kind of compulsory institutionalisation? The answer requires an understanding of positive as opposed to negative liberty. Negative liberty is merely the absence of external constraints or coercion. Positive liberty is about possessing the necessary intellectual, moral and psychological resources to be able to take responsibility for your own life and make your own choices. You cannot have a ‘free society’ if a large proportion of the population are incapable of governing their own lives. A properly functioning education system aims to equip people with the knowledge and skills needed to participate in modern liberal democratic society.

A healthy news, media and information ecosystem, like a healthy education system, is necessary in order to enable people to make informed choices and therefore participate fully in liberal democratic society. News media gives people important information about what is going on in the society around them, and importantly, gives them information necessary to participate in democratic decision-making.

In fact, the news media provides several functions important in a democracy:

- Informing the public – news media provides citizens with information about what is going on, allowing them to make informed decisions.

- Facilitating the formation of public opinion – Through news articles, opinion pieces, and debates, citizens engage in discussions and form opinions. This is very important because in a democracy, public opinion matters.

- Watchdog role – the news media hold the government and other institutions, officials and powerful people accountable by uncovering, investigating and bringing to public attention abuses of power, corruption and other cases of wrongdoing. This helps ensure transparency and maintain the integrity of democratic institutions.

- Ensuring viewpoint diversity – The media provides a platform for various voices, whether from different political ideologies, cultural backgrounds, or social groups. This diversity ensures a robust exchange of ideas, encourages critical thinking, and all going well prevents the media from becoming partisan or ideological.

- Facilitating debate and discussion – the media often provide a forum where different perspectives are aired and debated. This fosters critical thinking and informed debate.

- Setting the agenda – news media, whether we like it or not, or whether we think it is legitimate, set the agenda in terms of politics and public policy by determining which issues receive public attention.

- Acting as a bridge – the news media serve as a conduit between policymakers and the public. They convey policymakers statements and actions to the public, and can also help bring citizens’ concerns to the attention of policymakers.

- Fostering civic engagement – through coverage of elections, civic events, and community issues, the media encourages citizen participation. Informed citizens are more likely to vote, engage in civic activities, and advocate for policy change.

- Balancing Power – because of the influence it wields over public opinion, the news media is itself a powerful entity within democratic societies. When it is fulfilling its role properly, it can help balance power dynamics within society and ensure that no single entity: whether government, corporations, or individuals; holds unchecked authority.

- Fostering social cohesion – modern liberal democratic states are becoming increasingly ethnically and culturally diverse. Many observers think that consumption of shared news media can give people a shared frame of reference and thereby foster social cohesion. The risk here however is that this becomes Orwellian thought-control.

The things listed above are public goods which are important to the proper functioning of a democratic society. What is important to note here is that commercial incentives facing major news media providers do not necessarily align with the provision of these public goods (commercial incentives encourage media to attract as many eyeballs as possible for as much time as possible and then sell that ‘eyeball time’ to advertisers). In the economics literature, private markets are typically understood to underprovide public goods, because it is difficult to charge appropriately for them, and so typically public provision is recommended to increase their provision toward the socially optimal level.

This is, in fact, the rationale for providing public funding for news media in the first place; i.e. the public benefits journalism and news media provide, which are important to the functioning of a democracy, are underprovided by the market. That means public funding is needed to encourage more news and journalistic content that specifically provides these important benefits.

Most news providers in New Zealand are privately owned and run, but TVNZ and RNZ are publicly owned and still command significant audiences – TV1 is the most watched TV Channel and RNZ is arguably the most listened to radio.

Public media is media funded by the public through taxation, but is independent from direct government management and oversight: maintaining editorial independence is a crucial feature. This is what distinguishes public media from state media. RNZ is publicly owned and completely publicly funded. While TVNZ is publicly owned, but is a mixed model with both commercial and public funding.

An overview of New Zealand’s current regulatory regime for news media

New Zealand’s main instruments for regulating news and broadcast content are:

- The Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993, administered by the Office of Film and Literature Classification;

- The Broadcasting Act 1989, administered by the Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA); and

- Voluntary self-regulation, primarily through the New Zealand Media Council and the Advertising Standards Authority.

The Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 was intended to classify and restrict harmful content, primarily in entertainment media. It is most visible to the public through film and video ratings (e.g. PG13, R16 and R18), rather than through direct regulation of news content.

The Broadcasting Act 1989 provides the framework for regulating traditional broadcast media such as radio, free-to-air television, and pay television, as well as certain live-streamed online content. Under this Act, broadcasters must comply with the Broadcasting Standards Code, which sets expectations for balance, accuracy, decency, and social responsibility. These include standards related to warnings for offensive material, the protection of children, and prohibitions on promoting illegal or antisocial behaviour.

Of particular note is Standard 4, which prohibits broadcasters from encouraging discrimination against or denigration of any section of the community on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, race, age, disability, occupation, religion, culture, or political belief. While intended to protect vulnerable groups, this standard has in practice sometimes been interpreted in a way that discourages coverage of politically sensitive or controversial perspectives. There is therefore a reasonable argument for reviewing or removing this standard in order to strengthen freedom of expression in public debate.

Finally, enforcement of some key principles, particularly balance, is inconsistent. The Broadcasting Standards Authority seldom intervenes in cases of demonstrable imbalance, leaving the standard largely symbolic. This undermines public trust in the system and suggests the need for reform to ensure that regulatory frameworks protect both accuracy and freedom of expression in a genuinely pluralistic media environment.

Issues facing New Zealand’s news media

This section provides a brief survey of the major issues and trends facing news media in New Zealand, and provides commentary on how these issues may be affecting the news media’s ability to fulfil its proper democratic function, as described above.

Issue 1: Public trust in media is declining

Public trust in media in New Zealand is falling. This mirrors trends across most Western nations for most major societal institutions.

High levels of trust in news media are important in order for it to provide the public benefits outlined above. If people do not trust news media, it can lead people to seek out alternative sources of information – this often leads to people seeking sources of information that conform to their preexisting biases. This can lead to polarisation and fragmentation of media consumption and of society more generally, harming social cohesion. Media are also unable to fulfil their watchdog role or foster civic engagement when they are not trusted.

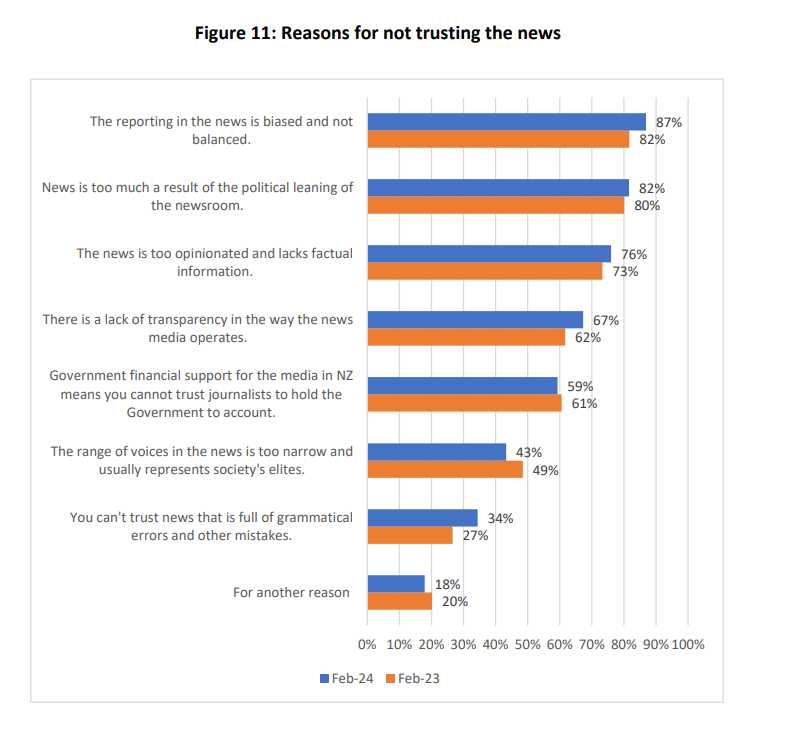

When asked why people do not trust the news, the main reasons given are bias and politicisation of newsrooms.

Issue 2: The conservative half of the political spectrum claim the media has a left-wing bias – evidence suggests they are correct

Several Media Bias surveys have been undertaken in recent years and have repeatedly shown that journalists and newsrooms tend to lean to the left in terms of political preferences. Journalists have self-reported a left-wing bias, public perceptions of bias have been shown to have increased, and there has been a corresponding decline in trust in media more generally.

In late 2022, the Worlds of Journalism Study found 81% of New Zealand journalists classified their political views as left of centre and 15% as right of centre. As right-wing commentator David Farrar noted in a piece for the Common Room, that 5:1 ratio was in stark contrast to the New Zealand population, with the 2020 election survey by Auckland University finding 28% of respondents identified as left of centre and 43% as right of centre.

The Pollster went on to note that New Zealand journalists were also far more likely to hold extreme left views than the rest of the population. 20% of journalists said their political views are hard or extreme left, compared to 6% of adults. On the other side of the spectrum, only 1% said their political views are hard or extreme right compared to 10% of the adult population.

Media bias has been noted to cause several very serious problems in society:

- Distorted information – leading to public misunderstandings or misinterpretations of events or issues.

- Confirmation bias – consumers of biased media may seek out and believe information that accords with their existing worldview, thus reinforcing it. This can lead to political and ideological polarisation in society.

- Erosion of trust in media and other institutions – when media continually slant their coverage against the values and interests of certain sections of the community, those sections tend to lose trust in the media.

- Warping democratic elections and public policy implementation – biased information can change voting decisions and policy preferences, interfering with the natural development of public opinion.

- Harms to social cohesion – through exacerbating political and ideological polarisation, as discussed above.

- Reduced quality of discourse – through prioritising entertainment over factual accuracy and reasoned analysis.

Public concern about media bias predates the COVID pandemic, but this problem was exacerbated during the pandemic by the large amounts of money provided to mainstream media outlets for COVID advertising, other advertising and the Public Interest Journalism Fund – which came with strings attached in terms of how media had to cover things.

The government spent $88 million between 1 March 2020 and 31 December 2021 on COVID advertising. Advertising spend across the public sector also increased markedly across the board, and the government also provided $55 million to the mainstream media in the form of the Public Interest Journalism Fund, which came with strings attached in terms of what could be reported, particularly on Treaty issues.

David Farrar’s company Curia Market Research conducted its own media bias survey in the form of a poll for the Taxpayers Union, focusing in on the PIJF. The poll of 1,000 New Zealanders found that 59% percent believed that government funding for private media companies undermined media independence, compared to 21% percent who believed it didn’t. Forty-four percent of those polled opposed the PIJF, while 24% supported it.

Issue 3: In today’s interconnected world, with internet and social media, journalism is now a public good

Public goods have the qualities of being non-rival and non-excludable. Non-rivalry means that one person consuming a good doesn’t stop another consuming it. Food is rival, enjoyment of the natural environment is non-rival. Non-excludability means that once the good is produced, it is impossible to prevent someone consuming it.

In today’s world with the internet and social media, where content can be shared and reshared online multiple times, journalistic content is effectively both non-rival and non-excludable – it is a public good. Public goods are not provided by the market, at least to the socially optimal level, because it is impossible for the producers of the goods to receive adequate compensation for them. Therefore, the most common solution is for them to be provided publicly through government provision and taxpayer funding.

Successive governments have recognised there is a problem with current regulatory and funding settings and have pursued policies such as the PIJF and the Fair News Digital Bargaining Bill to try and improve the media market. However, there are problems with these solutions. It may be the case simply that more government funding is required.

Issue 4: New Zealand may have a “natural monopoly” in television broadcast news

A second television news bulletin on Channel 3 has always struggled in New Zealand, both in market share and financial viability. Since the 1990s, successive operators – TV3’s 3 News, Newshub, and now ThreeNews – have faced persistent losses. This pattern suggests that New Zealand’s population and advertising base may be too small to sustain two competing nationwide television news operations.

In economic terms, this could represent a natural monopoly – a market where the high fixed costs of production (e.g., studios, satellite infrastructure, national newsrooms) and relatively low marginal costs mean that a single provider can supply the market more efficiently than multiple competitors. Television broadcast news exhibits these features, as audiences are limited and revenues are increasingly fragmented by online alternatives.

Where a natural monopoly exists, economic theory generally recommends some form of regulation or public-interest obligation to ensure socially optimal outcomes. Without competitive pressure, a sole provider may underinvest in news coverage or reduce quality to cut costs.

Issue 5: People are consuming news in new ways

New Zealand’s media ecosystem consists of television, radio, newspapers, online news providers, social media, and online streaming services.

The primary news mediums used to be television, radio and newspaper. But the internet has resulted in innovation and the creation of new mediums such as online news (e.g. Stuff), streaming services (e.g. Netflix), and social media (e.g. Youtube), all of which now threaten the dominance of traditional mediums.

Refer to NZonAir’s 2023 Where are the Audiences report for more information.

Issue 6: Citizen-journalism in New Zealand is thriving

The advent of social media, such as twitter (now X), and Substack, has allowed individuals to set up and contribute to public discourse without being a journalist, having name recognition, or having a large platform. Individual commentators, such as Philip Crump, now regularly break bigger stories than mainstream news providers. This is a tremendously positive development for New Zealand’s news ecosystem, and means New Zealanders aren’t as reliant on large media institutions to provide many of the public goods listed above.

Social media, due to its limited reach, is inferior to broadcast media in its ability to inform the public, shape public opinion, set the agenda, balance power or foster social cohesion; however, due to its interactive nature and the ability of users to participate in debate, rather than merely passively consume information, it is arguably a superior tool for performing the watchdog role, ensuring viewpoint diversity, facilitating debate and discussion, acting as a bridge between politicians and the public and fostering civic engagement.

On the negative side, social media has arguably contributed to the development of echo chambers, polarisation, a loss of social cohesion, and the proliferation of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

Issue 7: New media providers have recently been established and now cater to the previously underserved conservative section of the New Zealand public.

Social media has perhaps served to reveal an ideological segment of the market that was being underserved by existing media providers – i.e. conservatives. Part of the reason for this is that politically correct narratives had successfully demonised conservative views as racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, etc, making mainstream media institutions reluctant to cover their opinions sympathetically. However, now that the existence of this segment has been revealed by social media, providers such as The Platform and Reality Check Radio have been able to set up to cater to their views.

As with the development of social media, this is a mixed, though largely positive blessing – it has improved viewpoint diversity, facilitated debate and discussion about a wider range of issues and fostered greater civic engagement among groups previously underserved by traditional media. However, some have argued that it also has led to the creation of media echo chambers, heightened polarisation and led to a breakdown in social cohesion.

It is likely that the embedding of hate speech restrictions into Standard 4 of the Broadcasting Standards Code, Section 131 of the Human Rights Act, and a myriad of other places in New Zealand law, policy, journalistic practice and newsroom culture has contributed to conservative viewpoints being underserved and media being biased.

Problem definition

Publicly funded media in New Zealand is failing to provide the balance and viewpoint diversity necessary for liberal democracy to function effectively. This failure arises both from structural economic realities (public goods, natural monopoly) and institutional ideological bias.

As a form of information or content, news and journalism have always had the quality of being non-rival, but with the development of the internet and social media, it is now freely shared and commented on – this means, to a significant extent it has also taken on the quality of being non-excludable. This means it is effectively a public good. According to conventional economic theories, this means it will be underprovided in the private market, and there is a well-established economic rationale for public funding and/or provision.

However, there is currently a lack of viewpoint diversity and significant institutional bias against conservative viewpoints within the journalism undertaken by public media in New Zealand. This limits its ability to provide the benefits discussed above and threatens its democratic legitimacy.

If all taxpayers are required to pay for public media through their taxes, then all should see their values and worldview reflected back in the coverage. It is not fair or healthy for our information ecosystem for journalists – particularly taxpayer funded ones – to view themselves as enforcers of an elite ideological consensus. Instead, they should view themselves as servants of ALL New Zealanders and try to reflect the worldviews of all parts of New Zealand society fairly – even the conservative parts who hold views that some might consider racist, sexist, homophobic and so on.

Proposal

I propose a mixed model, where tougher regulatory oversight applies to public media, while private media remains largely unregulated.

The rationale for this is that publicly funded media is funded by ALL taxpayers. In order to provide the public good benefits identified earlier in this paper, it should be required to cater to the values and interests of ALL taxpayers. This means it should be balanced, unbiased and cover the full range of perspectives held by New Zealanders.

To give effect to this proposal, existing sources of media bias in law and policy need to be removed, and bias needs to be measured.

Removal of bias will require eliminating Standard 4 of the Broadcasting Standards Code which contains forms of hate speech restriction, and also eliminating other types of hate speech from New Zealand law, such as Section 131 of the Human Rights Act. Further investigation of journalism courses and schools could also reveal sources of anti-conservative bias that could be addressed.

Tougher controls will be needed over 1News and RNZ to reduce bias and ensure greater provision of journalism and news content that is in the public interest. Performance in terms of reducing bias and ensuring balanced coverage needs to be regularly monitored and reported on in public media. There must be enforcement of some sort – fines, denial of funding, negative performance reviews for management, etc. Because of the existence of institutional bias and resistance to a change in ethos, tools with teeth will likely be required to compel this change. The main levers available to influence 1News and RNZ are:

- Funding – The types of programming that are funded by NZ on Air and other groups.

- Regulation/standards – Currently the Broadcasting Standards Code contains hate speech restrictions in Standard 4 and the BSA has very limited teeth to enforce “balance”.

- Staffing – Changes could be made to senior management positions and the performance agreements they operate under.

A suite of greater controls need to be developed to ensure progress is made towards reducing bias. Officials should be tasked with developing this suite of tougher controls and enforcement mechanisms.

Some guiding principles are as follows:

- The goal is to reduce media bias, improve public trust, and provide the public benefits listed in the sections above.

- A clear separation between straight news and opinion and analysis should be enforced – New Zealand media has a tradition of a 6 O’Clock straight news broadcast, and a 7pm current affairs show. The maintenance of clear boundaries between straight news and reporting and opinion and analysis is important.

- Opinion journalism is fine, even helpful, but there must be a broad range of opinions showcased that are broadly representative of New Zealand as a whole – this doesn’t mean only providing the opinions of people “in the middle”, but ensuring the opinion from all parts of society and the political spectrum gets a fair hearing…even the racist, sexist and homophobic ones.

- Compliance with basic principles of journalistic integrity should be required: Seek Truth and Report It; Independence and Objectivity; Transparency and Accountability; Avoid Misrepresentation; Ethical Decision-Making.

These are all reasonable expectations that the public already have of journalists and public media, but at present there is little in the way of measurement, public reporting, incentives, or consequences if they are not followed.

In addition to new controls on public media, regulation of private media should be largely removed – if public media is to be tasked with providing news and journalistic content identified as having public good qualities, then an unregulated private media will be free to act as a critic and conscience ensuring it does so. Absence of regulation in private media ensures it can function as a sort of “safety valve” allowing new providers to be set up if a substantial section of the public finds their views uncatered to – this is arguably what happened with the establishment of The Platform and Reality Check Radio in recent years, and those media providers were able to provide some much needed viewpoint diversity and media criticism, particularly around biased coverage of so-called “woke” issues.

I do not propose changes to the existing Broadcasting Standards Regime apart from the removal of Standard 4 of the Broadcasting Standards Code, and a clarification that its scope only applies to traditional broadcast media, not podcasts or online media like The Platform and RCR.

Properly structured, the model outlined above would ensure publicly funded media is accountable to all citizens through regulation and performance oversight, while private media remains free to hold it to account, ensuring balance across the wider information ecosystem. In fact, properly structured, public and private media will be able to act as checks on each other, creating a virtuous circle.

Alternative courses of action

The government could consider several alternative approaches to address the issue of media bias and the provision of public-interest journalism:

1. Privatise and deregulate TVNZ and RNZ

Under this approach, TVNZ and RNZ would be sold into private hands and the Broadcasting Standards regime abolished. New Zealand’s major media outlets would then operate solely under commercial imperatives. Their funding and viability would depend entirely on audience size, advertising revenue, and commercial success.

- Pros: Reduces taxpayer burden; possibly encourages efficiency and innovation; aligns media incentives with consumer demand.

- Cons: Risks undermining the provision of public-good journalism, such as investigative reporting, coverage of a broad range of ideological and cultural perspectives, and civic education. Private outlets may prioritise entertainment or partisan content over socially beneficial reporting. Regional and niche coverage could disappear entirely. International experience shows that fully commercialized public broadcasters often cut back on content that is costly but democratically important (e.g., local news, science, or arts programming). Another problem is the appearance of violence, sex and nudity on daytime TV and radio due to the elimination of the Broadcasting Standards regime.

2. Regulate all media

This option would extend oversight and accountability standards, similar to those proposed for public media across the entire media ecosystem, including private news outlets and online platforms.

- Pros: Could theoretically ensure balance, fairness, and viewpoint diversity across the board. Creates a uniform standard of journalistic responsibility. Could also theoretically remove harmful material from online media.

- Cons: High administrative and enforcement costs; risk of overreach and censorship; may chill freedom of expression and reduce diversity of opinion. Regulating online media and citizen journalism would be particularly complex. Could also undermine recent improvements in conservative-leaning media provision, which have emerged precisely because private media have been relatively unregulated.

3. Maintain the status quo

Continue with current arrangements.

- Pros: Minimal administrative change; low political resistance; retains the benefits of innovation and viewpoint diversity in private media.

- Cons: Fails to address declining public trust and perceived bias in public media. Public media continue to serve some audiences better than others, undermining the legitimacy of publicly funded journalism. Over time, this may exacerbate polarization and reduce the effectiveness of public-interest media as a democratic tool.

Conclusion

The purpose of public media is to provide public benefits crucial to the proper functioning of democratic society. Currently, our publicly funded media is losing the ability to provide these benefits because of falling public trust, due mainly to bias. Existing sources of bias should be eliminated and stronger controls implemented to ensure balanced coverage that respects and serves the values and interests of ALL New Zealanders. Largely unregulated private media could then serve as a “safety valve” ensuring free speech, holding public media to account, and allowing new providers to be set up to cater to underserved sections of the community.