by William McGimpsey

Introduction

This White Paper offers an analysis and argument in favour of economic nationalism. It provides a brief theoretical sketch of what economic nationalism is, and how it differs from the economic policy approach currently dominant in the Western World, that of neoliberalism; it provides a historical analysis of the development of economic nationalist ideas and policies; provides a critique of reigning neoliberal approach; and provides some contemporary examples of where the nationalist approach has proven successful. The paper concludes by arguing the time is ripe for a paradigm shift in Western economic thinking away from neoliberalism and toward economic nationalism.

What is economic nationalism?

Economic nationalism is not merely a synonym for civic nationalism, although the term is sometimes used in that way by politicians, policymakers and academics looking to signal support for nationalism, while retaining rhetorical distance from the concept of ethnonationalism. Economic nationalism is just nationalist economic policy.

Conceptual framework

Economics, like other disciplines, is based on a series of foundational assumptions, the logical outworkings of which form much of the body of theory (with empirical work and continual refinement of models also playing an important role). The major branches of economics diverge primarily because of differences in foundational assumptions. For example, neoclassical economics assumes individuals are rational utility maximisers, while behavioural economics assumes they are only “boundedly rational”. And whereas the neoclassical school assumes markets are generally efficient, the Keynesian school assumes they can fail. These differing fundamental assumptions lead to quite different theoretical “schools” which produce quite different concrete policy recommendations.

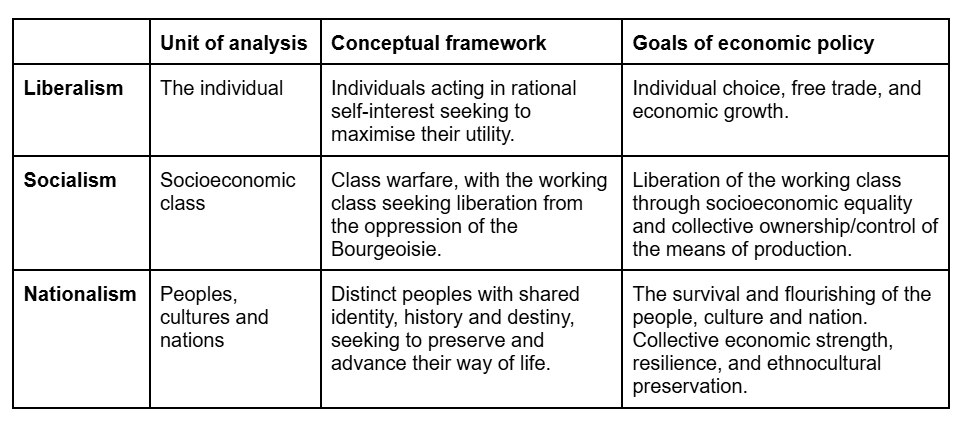

The field of economics in its entirety is very complicated with many schools, so to simplify the whole thing down, I’ll break it into three broad categories which I think are reasonably intuitive, map on well to people’s normative political commitments, and have pretty good trans-historical and cross-disciplinary applicability: liberalism, socialism, and nationalism:

- For the liberal, the world is a place where rational self-interested individuals seek to maximise their individual utility.

- For the socialist, the world is an arena of class conflict, where the proletariat struggle to liberate themselves from the economic and social oppression of the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production.

- For the nationalist, the world is a community of ethnically, culturally, religiously and linguistically distinct peoples, each seeking to preserve and advance their way of life.

Table 1 compares these theoretical approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of liberal, socialist and nationalist economic approaches

The status quo in much of the Western world is neoliberal economic policy with some socialist trimmings. Economic nationalism has been largely demonised and excluded from mainstream political discourse in recent decades, excepting some of the moves of the recent Trump Administrations.

The key principle motivating any economic nationalist approach is the promotion of the survival and flourishing of the people, culture and nation. In contrast to the liberal approach, it is the wellbeing of the collective that counts, not the freedom of the individual. Liberal economic approaches may sometimes be favoured by economic nationalists for their great ability to create wealth, but will be opposed where they undermine a nation’s cultural, moral, or demographic foundations. Likewise, economic nationalists may sometimes favour socialist economic approaches in cases where inequality has become so great as to harm the nation’s health and social cohesion, but will oppose them where demands for equality or collective ownership damage the nation’s moral/cultural/ethnic/religious foundations or collective economic strength.

Implications

These differences in first principles mean that countries with more economic nationalist policies are likely to:

- Balance individual economic freedom with the strategic needs of the nation – meaning that sometimes geopolitical, military and diplomatic priorities will come first.

- Prioritise the physical, demographic, moral, and spiritual health of the people over the individual accumulation of wealth or satisfaction of desires.

- Cultivate a degree of self-sufficiency in strategically important industries – such as food production, energy, and basic defence capability, regardless of economic efficiency (i.e. a nationalist economic approach would favour maintaining capacity in these areas even when they could be more efficiently produced elsewhere so as to preserve economic independence and resilience in times of crisis and conflict).

- More tightly screen foreign investment to ensure benefits accrue to the nation and its people rather than foreigners, and that strategically important firms, industries and infrastructure remain under national control.

- Reject immigration policies that lead to ethnic replacement, regardless of any claimed economic benefits.

A world of nationalist economies would sacrifice global economic efficiency in production in favour of greater self-sufficiency on the part of each nation: making each nation-state less reliant on the global economy and more resilient to global shocks, crises and conflicts. The efficiency of the global economy would be sacrificed, at least to a certain degree, to ensure the health and survival of the world's diverse peoples, cultures and nations, rather than sacrificing the health and survival of the world’s peoples, cultures and nations to the efficiency of the global economy, as we do at present.

Whether the efficiency of the global economy, or the health, survival and flourishing of individual peoples, cultures and nations should take priority is a key disagreement between liberal and nationalist approaches.

Typical policies

Nationalist approaches to economic policy often involve the following specific policies:

- Industrial policy – to support and improve the competitiveness of strategically important industries through subsidies, public investment, regulations and other policy tools.

- Tariffs and trade protectionism – to protect strategically important firms/industries (e.g. food, energy and basic manufacturing) from competition that threatens to drive them out of business.

- Restrictions on overseas investment – to protect strategically important firms/industries (e.g. infrastructure, media) from falling into foreign control.

- Policies to encourage domestic savings – to reduce reliance on foreign capital and vulnerability to its withdrawal.

- Buy national campaigns and use of government procurement to assist domestic industries.

- Restrictive immigration policy – to preserve ethnocultural identity, ensure social cohesion, and protect domestic workers from competition.

At this point, you should have a good working understanding of what economic nationalism is – from the differing normative judgements it is based on, to how these influence the general approach, and the specific policies that are typically implemented as a result.

Historical analysis

Now equipped with a basic understanding of what economic nationalism is, we can analyse its development historically.

Contemporary economists often present the neoliberal consensus and its assumptions as if they are universal truths, but this is not the case. Beliefs like the idea that individuals act according to rational self-interest, that free exchange is mutually beneficial, or that economic growth equals progress, are historically contingent – they are products of philosophical ideas that have a specific lineage, emerged only in certain times and places, and found acceptance only because they were suited to explaining and guiding policy in a particular set of historical circumstances.

In the ancient and medieval worlds for example, economics was not understood as a separate, technical discipline at all, but as an extension of ethics, law, and statecraft. Rulers sought not to increase wealth for its own sake, but to ensure stability, social harmony, and the flourishing of the realm under divine or natural law.

In ancient civilisations, “economic policy”, for the most part, consisted of central planning of agriculture and food security, tax collection (or tribute), regulation of trade…including slavery, and military provisioning. The goals were the preservation of the ruler's authority, maintenance of the social hierarchy, and, often, the survival of the peasantry.

Medieval Europe’s economy was structured by the feudal system. It was agrarian and land-based – kings granted land to nobles in return for loyalty and military service, while peasants worked the land and paid rents to the nobles. Kings also granted trade privileges, protected guilds, and regulated markets. Under Christian influence, economic thinking was oriented toward upholding a moral economy that ensured justice, charity, and social harmony, through practices like fair prices, honest labour, and bans on usury. The goal of policy was not to maximise individual utility or economic efficiency, but to ensure the right relationship between lords and peasants, merchants and monarchs, man and God.

The liberal conception of man as a rational self-interested utility maximiser, which forms the basis of modern economics, arose only in modern times through the philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Adam Smith. This idea would have been alien or anathema to people in the ancient and medieval worlds, for whom rationality was aimed at aligning the soul with virtue, or knowing God, rather than calculating outcomes or pursuing private advantage. For our ancient and medieval ancestors, the liberal conception of rationality and the ends of human activity would likely have been construed as pathology or sin.

Mercantilism: The First Nationalist Economic Model

The old feudal order began to break down in the late middle ages, and this process accelerated through the 16th and 17th centuries. Feudalism’s decentralised structure relied on local lords for military service and revenue, which made it poorly suited to funding the large standing armies, navies, and expansive bureaucracies which monarchs were increasingly developing in order to fight large and costly wars and manage growing trade and urbanisation. Mercantilism was adopted as the preeminent economic doctrine by the European powers (Spain, Portugal, France, England, the Dutch, Sweden, Denmark-Norway and Russia) from the 16th to the 18th century, because it both enabled and justified the rise of this new, more centralised form of social organisation, which we now call the nation-state.

Mercantilist economic policy aimed at the accumulation of gold and silver bullion. Modern economists sometimes express contempt with the preoccupation with the accumulation of bullion, characterising it as primitive or economically ignorant. But these criticisms are ideological and betray an ignorance of historical conditions and goals: as fiat currency did not exist at the time, gold and silver were the ultimate stores of value and means of exchange. Although other types of money and credit were coming into increasing use, they too were backed by gold and silver. The more widely gold and silver were accepted, the more useful they became as money, an example of the economic concept of network effects. This created path dependence, as states and merchants built institutions, trade systems, and pricing conventions around bullion, reinforcing its use.

What’s more, armies and navies ran on hard cash: so the possession of significant stockpiles of gold and silver allowed large militaries to be maintained, along with imperial outposts and administration – allowing a nation to effectively project “hard power”. Bullion could also be used in diplomacy – e.g. to subsidise allies to fight wars on your nation’s behalf, and allowed for “nation building at home”, funding civil servants, public works, and infrastructure. Thus historical circumstances resulted in a situation where the possession of large stockpiles of gold and silver gave a nation a decisive geopolitical advantage.

The private economy and the state were often deeply intertwined, so in addition to maximising the bullion in the state’s treasury, it was also thought beneficial to increase the amount in general circulation within the national economy. In order to achieve this, mercantilist nations sought to maximise exports, which brought more gold into the economy, and minimise imports, which led to less gold leaving the economy. To achieve this they used tariffs and quotas to minimise imports, and often chartered, regulated and monopolised trading companies to secure bullion and resources on behalf of the state. Colonialism played an important role: colonies were either direct sources of bullion, as the Americas were for Spain, or sources of raw materials that no longer had to be purchased with bullion, and could be used as inputs in manufacturing which were then exported to earn bullion.

Historical circumstances therefore led to the creation of the modern nation-state and the adoption of mercantilism as the dominant economic policy during this period, because mercantilism both facilitated and justified the geopolitical competition the European states were engaged in.

Mercantilism qualifies as a nationalist economic approach because it placed the survival, power and prestige of the nation, as a collective, ahead of the goal of allowing individuals to maximise their own wealth or utility: i.e. its goal was not consumer welfare, but geopolitical advantage.

The Liberal Turn: 19th-Century Free Trade Ideals

From the late 18th to mid 19th centuries, the world changed in ways that led to the abandonment of mercantilism as the preeminent economic doctrine. The Industrial Revolution led to a nation's industrial capacity becoming the decisive factor rather than its store of bullion as a measure of its national strength and ability to project power. Greater industrial strength allowed nations to produce more weapons, ammunition, ships, vehicles, planes, railways, infrastructure, food, clothing, fuel and so on. Industrial strength also tended to assist in achieving technological superiority and greater borrowing power, as lenders would lend based on a nation’s ability to pay the debt back with future output.

Along with these real world developments, enlightenment ideas reconceptualised the purpose of economic activity as meeting the wants and needs of individual consumers, rather than strengthening the power of the state. Thinkers like Adam Smith and David Ricardo argued that free trade increased general welfare by allowing nations to specialize according to comparative advantage.

As a result of these developments, Britain, the industrial leader of the age, embraced free trade unilaterally in the mid-19th century, removing tariffs on hundreds of goods. The decision was not due merely to liberal idealism: Britain had already achieved a dominant position in terms of industrial development and international trade – its industries were highly competitive and not in need of protection, and its colonies and empire provided guaranteed markets for its goods and valuable sources of raw materials. Given its dominance was already assured, Britain could afford to embrace free trade geopolitically.

Other Western nations were slower to follow Britain in adopting free trade. France, Germany, and the United States continued to use tariffs to protect their infant industries. However, global trade expanded rapidly in this era – growing roughly 25-fold between 1850 and 1913.

The Protectionist Revival: Late 19th to Early 20th Century

Despite liberal advances, by the 1870s a wave of protectionism swept across much of the West. The Long Depression (1873–1896), rising agricultural imports from the Americas, and increasing industrial competition spurred governments to shelter their economies. Germany, under Bismarck, introduced high tariffs to protect farmers and steel producers, and the U.S. raised tariffs under the Dingley Act, maintaining duties above 40% in some cases. Britain remained largely free-trading until the 1930s, and its GDP grew steadily at around 2% per year, but late-developing countries like Germany and the U.S. grew even faster under more protectionist regimes.

The high-growth performance of Germany and the U.S. during this time undermined support for liberal economic dogma. Both countries achieved growth rates of 3-4% annually, surpassing the growth rates of Britain’s more liberal economy. Economic nationalism, in these cases, was associated with successful industrial catch-up. The success of Germany and the USA foreshadowed what developing Asian economies like Japan, China, and South Korea would be able to accomplish in later decades with similar economic nationalist policies.

The Great Depression and State Planning

The Great Depression of the 1930s marked a dramatic turn toward nationalist economic planning. The collapse of world trade and the failure of laissez-faire orthodoxy led nations to retreat behind tariff walls and embrace state intervention. In 1930, the U.S. passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, triggering retaliatory protectionism and shrinking global trade by two-thirds by 1933. Germany, under Hitler, pursued autarky and state-led reindustrialization. Britain abandoned free trade and formed the Sterling Bloc, tying trade to the Empire.

Economic growth in the 1930s was uneven. The U.S. experienced sluggish recovery until World War II, but Germany saw rapid industrial expansion (albeit fuelled by rearmament and debt).

Postwar Liberal Order with National Underpinnings (1945–1970s)

After 1945, the United States led the construction of a liberal international order, founded on the Bretton Woods system, GATT, and Marshall Plan aid. The aim was to prevent a return to nationalist rivalries and to integrate the West economically against the Soviet threat. However, this liberalism was qualified: Western governments retained control over capital flows, exchange rates, and domestic industries.

This era, often called the Golden Age of Capitalism, saw remarkable growth: Western European economies grew at 4–5% per year, Japan even faster, and the U.S. averaged around 3.5%. The combination of regulated markets, social welfare, and managed trade proved highly effective. Some nationalist policies persisted in practice, e.g., France’s state-led industrial planning, and U.S. government R&D spending, but within a liberal framework.

Neoliberalism and Globalization (1980s–2008)

Economic stagnation and inflation in the 1970s led to a neoliberal revolution in the 1980s. Leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher championed free markets, deregulation, and privatization. The World Trade Organization (WTO) was established in 1995, extending liberal rules globally. The European Union deepened economic integration, and NAFTA linked North America.

This era of hyper-globalization saw falling tariffs, offshoring, financial liberalization and accelerated rates of immigration and demographic change. World trade as a share of GDP rose dramatically. While global GDP grew, the benefits were unevenly distributed. Western working-class industries declined as production moved to China and other low-wage countries, fuelling economic discontent.

Return of Economic Nationalism (2010s–present)

The 2008 global financial crisis exposed vulnerabilities in the liberal order. Rising inequality, job losses, and the erosion of industrial bases sparked a populist backlash. In the 2010s, Western nations began turning back toward economic nationalism: Brexit in the UK, Trump’s tariffs and reshoring efforts in the U.S., and EU policies promoting strategic autonomy.

The COVID-19 pandemic and US-China tensions accelerated this shift. Countries began rethinking global supply chains and reasserting state roles in key sectors. Even previously liberal governments embraced industrial policy and strategic trade tools.

Conclusion

Western economic history reveals a cyclical pattern: liberal economic approaches emphasising free trade have been adopted only in very specific geopolitical circumstances – when a dominant power has achieved geopolitical hegemony. This was the case when the British Empire unilaterally introduced a free trade approach in the mid-19th century, and again when the US achieved global hegemony post WWII. However, in times of great power competition between nation-states, nationalist economic approaches have been favoured. This is rational, and to be expected, if one accepts the principle that national survival is, and ought to be, a higher priority than individual consumer welfare, and so only in times where the former is assured should policies be introduced which prioritise the latter.

Liberal economists of course do not accept this, but that is because they are trapped within the logic of their own basic assumptions: often they are unaware that they are even making those assumptions…they take them for granted. Part of the task then, is to try and convince them, through little historical analyses like this, that liberal assumptions about the primacy of maximising individual consumer’s utility are merely assumptions, that they can be questioned, that they are historically contingent rather than universal, that for most of history they have not been found persuasive, that other goals such as national survival, strategic competition, and sustaining the moral-cultural basis of the community have taken primacy…and for good reason.

Criticisms of the Neoliberal Consensus

The neoliberal policy consensus has come under sustained criticism from both left and right in recent decades. Critics on the left have argued that neoliberal policies have resulted in increasing inequalities in wealth and income that are becoming so extreme they threaten to undermine the basic democratic order premised on the idea of equality of citizens. Critics on the right point to the ways in which neoliberal policies around immigration have undermined Western demographics and culture; how foreign investment policies have undermined economic sovereignty; and how globalisation has undermined both the legitimacy and the effective sovereignty of the nation-state itself as an institution. The neoliberal consensus has also been criticised on a purely empirical basis for failing to achieve its own goals of strong economic growth as effectively as countries that have adopted other policy approaches.

Market failures and the necessity of planning

Neoliberal economic policy depends on idealised assumptions about how markets work that don’t always hold in practice. In particular, that markets are always the best and most efficient way to allocate resources. This isn’t always true.

A well-functioning market is one that allocates resources efficiently: by matching supply with demand, promoting innovation, and maximizing societal welfare through decentralized decision-making. For this to happen, several conditions must be met: competition must be robust; all participants must have access to reliable, symmetric information; property rights must be well-defined and enforceable; there must be no significant externalities (costs or benefits not reflected in prices); and transaction costs must be low. Under these conditions, price signals coordinate individual choices into an efficient outcome, as famously described by Adam Smith’s “invisible hand.”

However, when these conditions break down markets tend to misallocate resources or fail altogether. Common failures occur in the presence of externalities (e.g., pollution), public goods (e.g., national defence, basic research), asymmetric information (e.g., in healthcare or finance), natural monopolies (e.g., utilities), or coordination failures (e.g., in large-scale infrastructure or training systems). In such cases, private actors acting in their own interest cannot produce outcomes that are socially optimal, and state intervention becomes necessary.

Several sectors of the economy exhibit these problematic conditions. Education and healthcare are characterized by long-term benefits, unequal access to information, and externalities – making them prone to both underinvestment and inequitable distribution when left to the market. Research and development, particularly in early stages, often generates knowledge spillovers that firms cannot fully capture, leading to chronic underfunding without public support. Infrastructure, such as roads and public transport, often involves long timeframes and large upfront costs that require coordinated planning which private markets are not well-positioned to deliver. Markets also consistently fail to price in ecological costs.

By attempting to withdraw the state from these areas, neoliberal policy leaves essential social and strategic needs unmet. It results in chronic underinvestment in public goods and long-term capacity. It allows inequality to widen, housing to become unaffordable, critical industries to be offshored, and environmental degradation to accelerate. Neoliberalism also treats economic resilience and national capability as afterthoughts.

In short, neoliberalism's insistence on market primacy blinds it to other important conditions necessary for long-term prosperity: stable institutions, public investment, long-term planning, and a coherent national strategy.

The theory of comparative advantage revisited

Ricardo’s original theory of comparative advantage held the factors of production, capital and labour, to be immobile between countries. However, under conditions where capital and labour can move, as occurs in the real world, the conclusions about the universal benefits of trade are much more tenuous.

Modern models that account for factor mobility still show potential global efficiency gains from free trade, especially through better allocation of capital, lower consumer prices, and expanded markets for firms. However, distributional effects are larger, and national outcomes vary more widely: gains are often concentrated (e.g. in multinational firms or capital-owning elites); workers and specific industries may suffer serious harm; there is no guarantee that a country will gain more from trade and capital mobility than from a carefully managed industrial strategy.

Global Trade and Conflicting National Interests

Ralph E. Gomory and William J. Baumol, in their book Global Trade and Conflicting National Interests, challenge the classical view that international trade is universally beneficial. Traditional trade theory, rooted in Ricardo's comparative advantage, assumes constant returns to scale and perfect competition. Under these conditions, all nations are said to benefit from free trade by specializing in what they do best. However, Baumol and Gomory introduce a more realistic framework – one that accounts for increasing returns to scale and imperfect competition, which are typical in many modern industries such as technology and advanced manufacturing.

Their central argument is that trade can produce conflicting outcomes between what is good for the global economy and what is good for individual nations. In their models, some countries can gain dominant positions in high-return industries, securing long-term economic advantages. Meanwhile, other nations may be pushed into specializing in low-return sectors, leading to persistent underperformance. This means that even as global output increases, the distribution of gains can be uneven, and some countries may end up worse off than if they had pursued more self-sufficient strategies.

They argue that comparative advantage is not a given fixed by natural endowments, but rather something that is determined by a country's pathway of industrial development. Countries that have a significant pool of human and physical capital specialised in areas that are transferable to industries of the future, find themselves better positioned to begin production in those industries, and scale up production to efficient levels where economies of scale are reached, thus locking out future competitors. This introduces a degree of competitiveness and rivalry into the international trade picture, that means government directed trade and industrial policies can have value.

Crucial to Baumol and Gomory’s theory is the concept of “ladder externalities”. Some industries have technological spillover effects, and/or develop skills and human capital that help upgrade the economy over time. This occurs through technological spillovers and by positioning the economy so it has the skills, capital and technical capacity that can be easily transferred to newly developing industries. These types of industries are strategically important to the economy and nation. However, their benefits do not accrue solely to their current owners. Hence they have positive externalities, and there is a prima facie case for government involvement to ensure they set up in your country and are retained.

The implication is clear: countries cannot rely on free trade alone to secure their economic futures. Instead, they may require strategic industrial policies to either retain or build competitive advantages in key sectors. In this light, trade is not always a win-win scenario; it can be a zero-sum competition over the most lucrative segments of the global economy.

Ultimately, the theory reintroduces national interest into trade policy, offering a powerful intellectual foundation for those who argue that unfettered globalization can undermine national prosperity.

The economic success of non-conformist countries

Several countries have adopted strategically protectionist approaches – particularly during their early stages of industrial development – and have outperformed countries that pursued more orthodox free trade policies. The clearest examples come from East Asia. Countries like Japan, China, South Korea, and Taiwan, pursued export-oriented industrialization, but crucially, this was not based on free trade in the classical sense. These countries protected domestic industries, used tariffs and subsidies, and guided capital and credit toward sectors deemed strategically important (e.g. steel, electronics, automobiles).

In contrast, many countries in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, which embraced liberalization in the 1980s and 1990s under the influence of the IMF, World Bank, and WTO, have experienced sluggish growth, deindustrialization, and growing inequality. Economists such as Ha-Joon Chang, Dani Rodrik, and Alice Amsden have argued that the success of protectionist East Asian economies is not coincidental, and that imposing free trade on poor countries too early can lock them into low-value-added sectors like raw material exports, preventing them from climbing the industrial ladder.

The evidence suggests that, at a minimum, timely and strategic deviations from free trade orthodoxy can yield better long-term outcomes than adhering strictly to free market doctrines, particularly for nations trying to catch up economically.

Mainstream economists often accept the empirical success of these countries but argue that trade protectionism itself wasn’t decisive, and that their success was due to their strong institutions, culture (e.g. focus on education, strong work ethic and high savings rates), and prudent macroeconomic management, but even if we accept this conclusion, economic nationalist policies around restrictive immigration, and the preservation of traditional values and culture deserve a lot of credit for driving these outcomes.

Contemporary economic nationalist success stories

Several nations currently adopt economic nationalist policies and manage to economically outperform Western states with neoliberal policies, while at the same time preserving their people, culture and way of life. Here are a few key examples:

South Korea

South Korea is often cited as a textbook case of successful economic nationalism. It has followed a strategic, state-guided capitalist model since the 1960s, with the government directing credit, protecting infant industries, and supporting key sectors such as steel, shipbuilding, electronics, and automobiles in order to achieve export-oriented growth. South Korea has a coordinated industrial policy, subsidises important national businesses like Samsung and Hyundai, and imposes performance requirements on firms in exchange for state support. While the country has liberalized over time, it still maintains strategic government involvement in technology, defence, and innovation sectors, which ensures national control over core capabilities.

As a result of these policies, South Korea achieved an annual GDP growth rate of approximately 7% between 1961 and 2023 – 8-10% from the 1960s-1980s and 3-4% since 2000 (World Bank). This transformed the country from an agrarian nation to an industrial and technological powerhouse. In 2023, South Korea had a GDP per capita of $37,675 in nominal terms, and an average wage of $49,062 in PPP terms. It is a world leader in semiconductors, shipbuilding, and electronics.

China

China’s economic model is based on state-led capitalism, where strategic sectors, such as technology, energy, and banking, are dominated by state-owned enterprises. Chinese industrial policy involves providing massive subsidies and support for key industries such as semiconductors, 5G telecommunications, and dual-use military technology. Tariffs and import restrictions are used strategically to protect domestic industries, and foreign firms wishing to do business in China are often required to partner with local firms to facilitate technology transfer and encourage growth in the capability of domestic Chinese firms.

As a result of these policies, China has experienced what analysts have called the “Chinese economic miracle” – sustained high growth rates averaging approximately 9% per annum from 1978-2010 (growth has slowed more recently, with rates of 4.8-5% in 2023-2024). In the course of 40 years, these growth rates have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and into middle class status and enabled China to transform itself from an economic backwater to the second-largest economy in the world – now challenging the US for global dominance.

Singapore

Singapore’s economic policy approach blends free-market principles with strong state guidance, strategic planning, and selective intervention. Since gaining independence in 1965, the government has pursued export-oriented industrialization, foreign direct investment attraction, and infrastructure development, while maintaining a reputation for low corruption and efficient public administration. Through sovereign wealth funds like Temasek Holdings and GIC, the state plays a significant role in owning and managing major domestic firms across sectors such as finance, telecommunications, and transport. Policies emphasize human capital development, high-value industries (like biotechnology, finance, and tech), and tight labour market controls to protect jobs for Singaporeans. Singapore’s model is often described as “state capitalism” or “pragmatic economic nationalism,” where national interests are prioritized through a strategic approach to global economic integration.

These policies have propelled Singapore from a developing economy, to one of the world’s most prosperous countries today. GDP growth averaged approximately 6-7% from 1965-2000 during rapid industrialization, and in recent decades from 2000-2023 has averaged 3-4% annually. This ranks it somewhere between 4th-6th in the world in terms of GDP per capita – one of the world’s best performing economies.

Taiwan

Taiwan’s economic strategy has been characterized by a blend of export-oriented industrialization and strategic state intervention. Since the 1960s, the government has prioritized the development of high-tech industries, investing heavily in education and infrastructure to support this goal. State-backed institutions, such as the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), have played a pivotal role in fostering innovation and facilitating technology transfers. This approach has positioned Taiwan as a critical player in global supply chains, particularly in the semiconductor industry, with companies like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) leading the charge.

As a result of these policies, Taiwan has achieved economic growth averaging 6-7% from 1960-1990, and 3-4% since 2000. Taiwan’s GDP per capita reached approximately $34,924 in 2025 (IMF).

Israel

Israel’s economic policy is characterized by a blend of free-market principles and strategic state support, particularly in high-tech and defence sectors. The government actively fosters innovation through initiatives like the Israel Innovation Authority, which provides funding and support to startups and research institutions. This approach has positioned Israel as a global leader in technology and innovation.

Israel is renown as the “Start-Up Nation,” and boasts the highest number of startups per capita globally. The tech sector contributes significantly to the economy, with high-tech services accounting for a substantial portion of exports. Israel’s defense sector is also a major player globally, with companies like Elbit Systems and Israel Aerospace Industries leading in the production and export of military equipment, including drones and missile systems.

Over the past decade, Israel has maintained an average real GDP growth rate of approximately 3.5-3.9% from 2013-2022. Growth slowed in the last few years primarily due to geopolitical tensions and conflicts. Israel’s GDP per capita was around $54,370 in 2025 (IMF) significantly higher than the global average

Norway

Norway’s economic policy blends free-market capitalism with strong state involvement, particularly in strategic sectors like energy. The government maintains significant ownership in key industries, most notably through Equinor (oil and gas) and Statkraft (renewable energy), as well as the infrastructure and finance sectors – ensuring national control over vital resources. A hallmark of Norway’s approach is its sovereign wealth fund, the Government Pension Fund Global, which invests oil and gas revenues internationally to stabilize the economy and safeguard wealth for future generations. Though engaged in global trade, Norway is not a member of the European Union, allowing it to maintain protective policies for domestic agriculture and fisheries. The country also features high taxation and a robust welfare state, redistributing income to support social cohesion and economic stability. This model, often referred to as the “Nordic Model,” exemplifies a pragmatic form of economic nationalism that balances openness with strategic sovereignty.

Over the period 1971 to 2023, Norway has sustained an average GDP growth rate of 2.77%, while maintaining an extensive social welfare system and relatively low income inequality. It had a GDP per capita of $90,000 in 2025 (IMF), and an average wage of $65,000-$70,000 in 2023 (OECD estimates). It also consistently ranks near the top of the ranking in the Human Development Index (HDI)..

The meaning of economic nationalism’s success

These examples show that economic nationalism doesn’t just ensure the survival of peoples, cultures and ways of life – it outperforms neoliberalism on its own terms. As the work of Robert Putnam and others on the effects of diversity on society has demonstrated, countries that protect their ethnocultural identity are better able to maintain social trust and strong institutions, which enables greater levels of cooperation and agreement on national interests, smarter investment, better governance, and more resilient growth. Far from being a tradeoff, ethnocultural continuity and economic success go hand in hand.

In contrast, the neoliberal emphasis on maximising consumption at the level of the atomised individual has hollowed out Western economies, facilitated mass immigration and demographic replacement, fractured our societies, and left us vulnerable to geopolitical shocks and cultural dissolution.

Conclusion

Economic nationalism is not stupid, backward or economically illiterate. It is an approach that prioritises the survival, health and wellbeing of the nation over economic growth and consumer choice. These are normative judgements that liberal economists cannot refute, and that in a free and democratic society members of the public can freely embrace if they feel they better reflect their priorities. Historical analysis reveals that the normative judgements underpinning economic nationalism are historically more normal than those underpinning liberalism, and what’s more, economic nationalism has been especially favoured by nations in periods of great power competition – contemporary policymakers should take note given that US global hegemony is under increasing pressure from a rising China, Russia and others and the world is becoming more multipolar.

If that isn’t enough, the criticisms, both theoretical and empirical, of the neoliberal consensus have been mounting, and many east Asian nations that have adopted economic nationalist policies have outperformed western economies that are operating on neoliberal principles.

The time is ripe for a paradigm shift in thinking on this subject throughout the Western World. Decades of neoliberal economics in the West have left our nations weakened geopolitically and our populations weakened spiritually. Continuing to operate on the current paradigm risks the death of the nation-state as an institution, the death of the peoples and cultures they were built to defend, and the end of our great inheritance of Western Civilisation.

Solzhenitsyn put it best:

“The disappearance of nations would have impoverished us no less than if all men had become alike, with one personality and one face. Nations are the wealth of mankind, its collective personalities; the very least of them wears its own special colours and bears within itself a special facet of divine intention.”

Originally published on The Conservative Network.